If you ask a UX professional what UX strategy is, you’d get answers as widely spread as hippo poo, of which the majority would be vague. Why? Because strategy is a confusing catch-all phrase, but still we want to include it in our skill set. Because it’s expected of us:

Jerome Kalumbu

I’m guilty of this; calling myself a design strategist but secretly hoping no one would call me out on it. If someone did, I would probably say something about defining the right approach for the target audience. That isn’t wrong per se, but what was missing was a clear definition of strategy, and the methodology to execute it.

To redeem myself I picked up one of the top-rated books on strategy and started to educate myself. Actually, the very first thing I did was to google ‘UX strategy’ but what I found was more confusing than helpful since everyone got their own take on it. Some say it’s a business strategy, others call it a plan, and if you look somewhere else it’s an alignment of the product vision with its users.

I don’t mean to bash these definitions in any way – in their own context they make perfect sense. But with so many answers out there, the only thing I could do to truly own the topic was to dissect it and shape my own opinion. So, based on the definition of strategy in the book Good strategy Bad strategy by Richard P. Rumelt, I did my best to really understand how I can use strategy in product design without the risk of losing face.

Strategy is a 3-step process

‘Strategy’ is a bit like ‘UX’; it gets thrown around a lot without much thought of what it actually means. Good strategy requires hard work, but strategy on a theoretical level isn’t difficult – it will sound all too familiar to anyone with experience in product design. Because, without knowing it, we’ve been doing strategy all the time. This is how strategy is defined in Good strategy Bad strategy:

- Diagnose the situation to understand what’s going on.

- Choose the overarching approach that will provide the most leverage.

- Define coherent actions that executes the approach.

Sounds familiar? This is pretty much textbook any design process I’ve come across. [Discover – Design – Deliver], Design Thinking, Lean UX, Design sprints, Double Diamond… they all have these basic steps embedded in the process.

The conclusion: Our design process is strategy in itself.

Let’s go back to our definition of strategy and relabel it:

- Define a problem space and gather insights to understand it.

- Explore possible approaches to solve the problem, and based on the insights, pick the one most likely to achieve desired results.

- Come up with a design plan with all the actions needed to execute the approach until measurable results have been achieved.

Admittedly, step two is where the real ’strategy’ work comes in, but Rumelt is quick to mention that step two is not enough to define a good strategy. Just as I mentioned in this article, the beginning and the end are the two most important steps of any project – we need step one and three in order to define and execute step two, aka ’the strategy’.

How to think about strategy as a product designer

For sure we can talk about UX strategy, but just like an ill-defined design process it will bring little to no value to the project. If we want to talk about strategy in a product design setting we need to break it down into smaller parts.

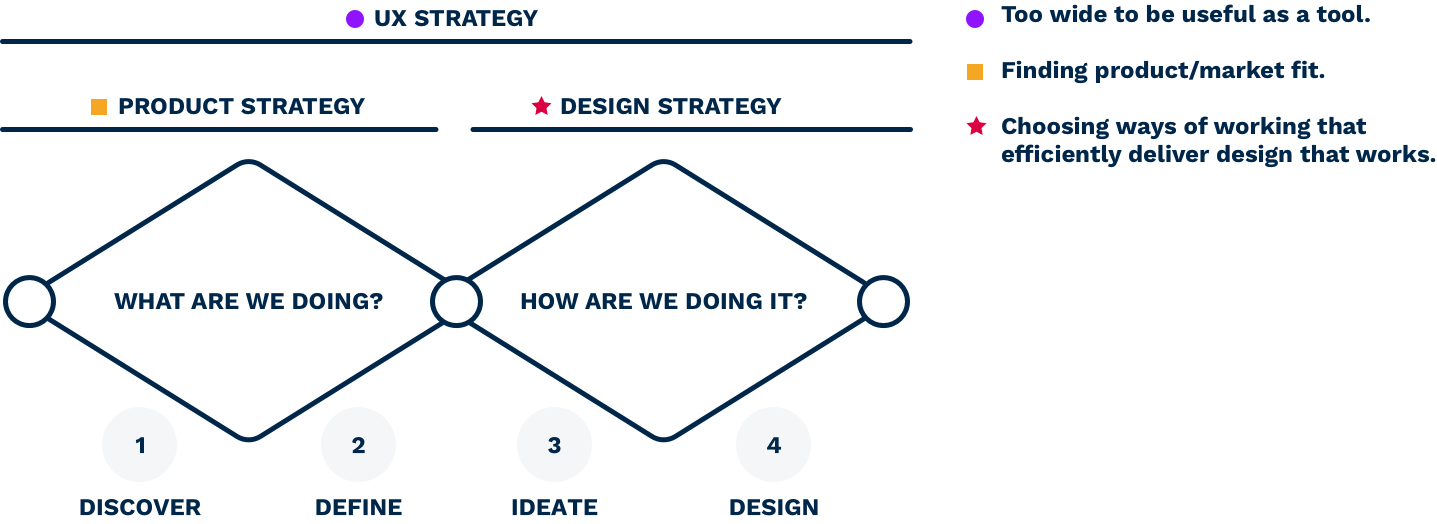

Using the Double Diamond product design process I propose thinking about UX strategy in two steps; Product strategy and Design strategy. Hear me out though, this is not only word-smithery. It’s my attempt to break something too complex into something usable.

UX strategy = The complete design process.

This seems to be aligned with the definition outlined in the book UX Strategy: How to Devise Innovative Digital Products that People Want by Jamie Levy:

UX strategy is […] being able to research what’s out there, analyze the opportunities, run structured experiments, fail learn and iterate until you devise something of value that people truly want.

Product strategy = The first diamond (What are we doing?), where the strategy part is choosing what to focus on to reach product/market fit.

Out of all steps, this is by far the hardest to get right. If there is a secret sauce to UX strategy, this is where you’ll need it. Considering how many established companies that become obsolete, and startups that pivot time after time, it’s clear that this is more gambling than science – the key is to better your odds with step one.

Design strategy = The second diamond (How are we doing it?), where the strategy part is your approach to design.

This will probably be a combination of tried and tested ways of working: Lean UX, Mobile first, Atomic design etc. Doesn’t sound very strategic, does it? But imagine designing without these approaches in place and you can see where the value of design strategy comes in.

Step two and three in the design strategy actually come before step one and should be fairly rigid from project to project. Design strategy is not about choosing the correct design – it’s about choosing the methods that help you choose and efficiently execute the correct design.

Let’s look at a practical example.

Case study: The UX strategy of a startup

Söber is a company offering chauffeurs to intoxicated people who need to get themselves and their car back home safely.

By exploring the opportunity space, they’ve found a market in mid-sized towns with poor public transport and no competition from online cab companies. Furthermore they know that the most receptive target groups are couples and groups of girlfriends dining out in the weekend.

Based on these insights, the approach for going live and testing their product/market fit is to launch a trial in a region with three mid-sized towns close to each other. This way they can recruit drivers that can serve all three towns. Rather than doing the heavy up-front work of an in-house infrastructure, third-party solutions and manual work will be used during the trial.

On the end-user side, the approach is to make an app available for download on Apple’s Appstore – a decision based on the target groups’ phone preference and the fact that the service needs to be accessible on the go and utilise positioning technology. Both target groups will be included in the app design and marketing efforts as the benefit of a larger user base is deemed greater than the additional cost of targeting two separate segments.

The plan to execute this approach includes recruiting the drivers, marketing the service, integrating a customer-driver matching backend, and building the consumer facing app.

As you can see, the product strategy branches out into different tracks, of which the consumer-facing app is one. Let’s take a look at that one.

From the product strategy, the product design team of Söber has the commercial and technical requirements to understand what the app needs to do.

Step one in the 2nd diamond seeks to understand and explore the challenge in a user-centric way. If there are enough insights gathered already, the team could move on to explore various directions the app could take. In Söber’s case, the app isn’t yet specified down to the specific features, and the team needs to do another iteration of the 1st diamond. They do this to form and validate hypotheses around the use of the app.

Do couples bring their children, meaning they’ll need an option for child seats?

Would a group of women feel more comfortable if they could choose a female driver?

Is cost-splitting essential for the app’s success?

Once the team has a good grasp of the value proposition and key user journeys, they can move into exploring design options. As they are integrated with an agile development team, they do this feature by feature, delivered in sprints and user tested before build.

To conclude

Reading Good strategy Bad strategy and writing this article has helped me ironing out a lot of the kinks in my understanding of strategy and how it is applied to product design. Although good strategy is needed in every project, talking about strategy in any form is a bit like talking about UX – a term so inflated that it has almost lost its value.

As designers we should remember that our end-to-end design process is strategy work in action. We can almost always replace ‘strategy’ with ‘approach’ to demystify our design documentation and presentations. Likewise, there’s nothing wrong with asking someone to clarify what they mean with strategy if you see it in their material.

Hopefully reading this has been informative rather than adding more confusion to the matter. Everyone has to shape their own understanding of the world, and I’m not here to say I’m speaking the Truth – But it is my take on it. For now.