Don’t get stuck in ‘discovery’ with insights no one asked for

This article is written from a corporate in-house point of view. If you work in a consultancy firm you’ll undoubtedly relate to this. If you work in an agency there might still be some takeaways worth your time.

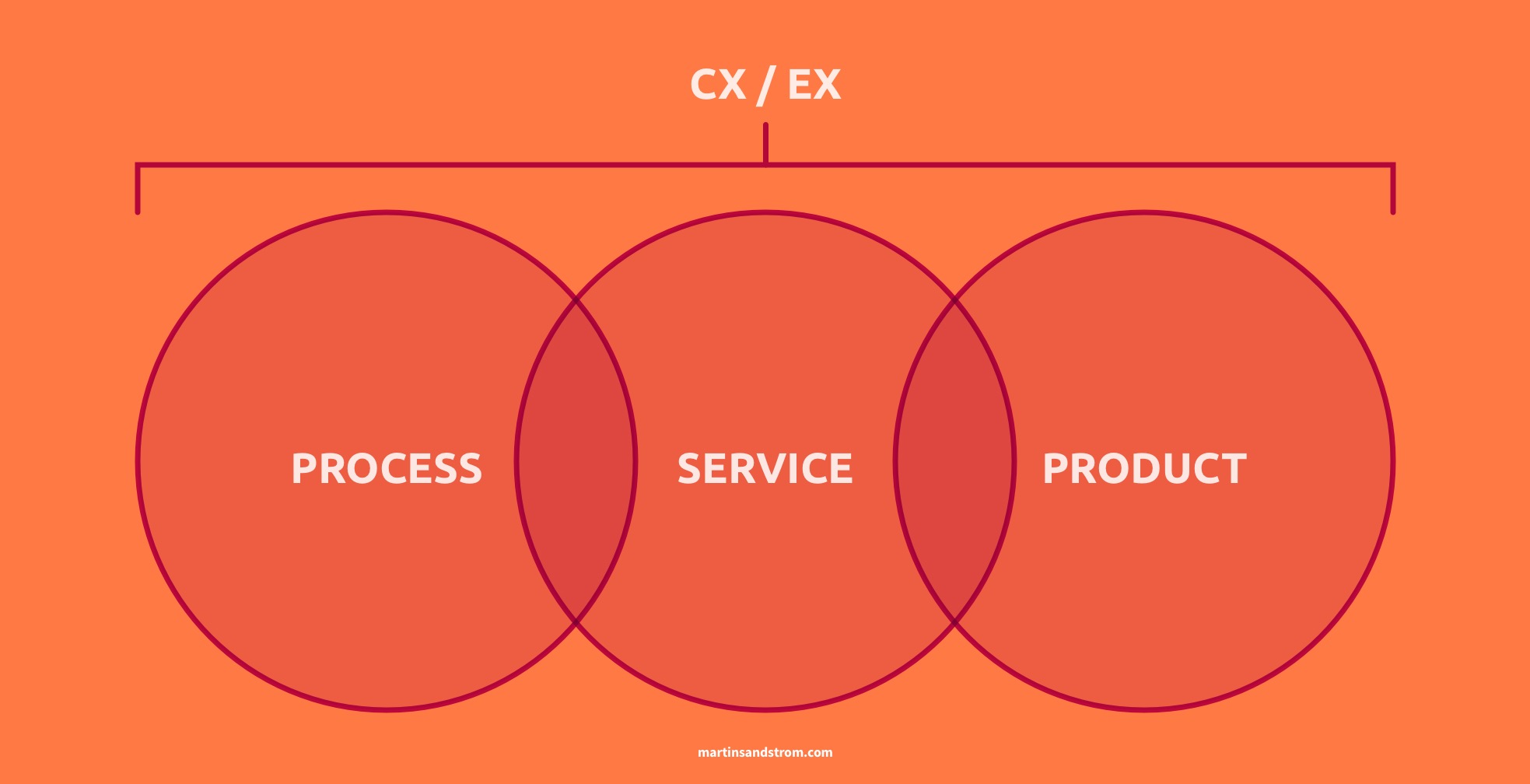

As designers selling our services we put so much emphasis on the fact that we’re problem solvers that can solve systemic problems. We can do more than make things look pretty. We understand business and we can talk strategy. We want a seat a seat at the adult table, God dammit!

That’s usually not how our non-designer colleagues or clients see us. So it’s been up to us to sell design as a tool for business and service development. IDEO did the heavy lifting with Design Thinking. Google Ventures did wonders for templating creative workshops and rapid prototyping. The Double Diamond, heavily used and popularised (but not invented as many seem to believe) by the British Design Council has been adopted and used for communicating design process to non-designers more than any other design process I can think of.

We’ve come up with all these fancy models, frameworks, processes and methods to allow us to get a foot through the door into the early discovery of a project. In order to pause for a moment and ask:

“Are we solving the right problem?“

Often the answer will be:

“Of course we are. Us adults have thought about this and we know what needs doing. Now go and build it for us. And make it pretty.“

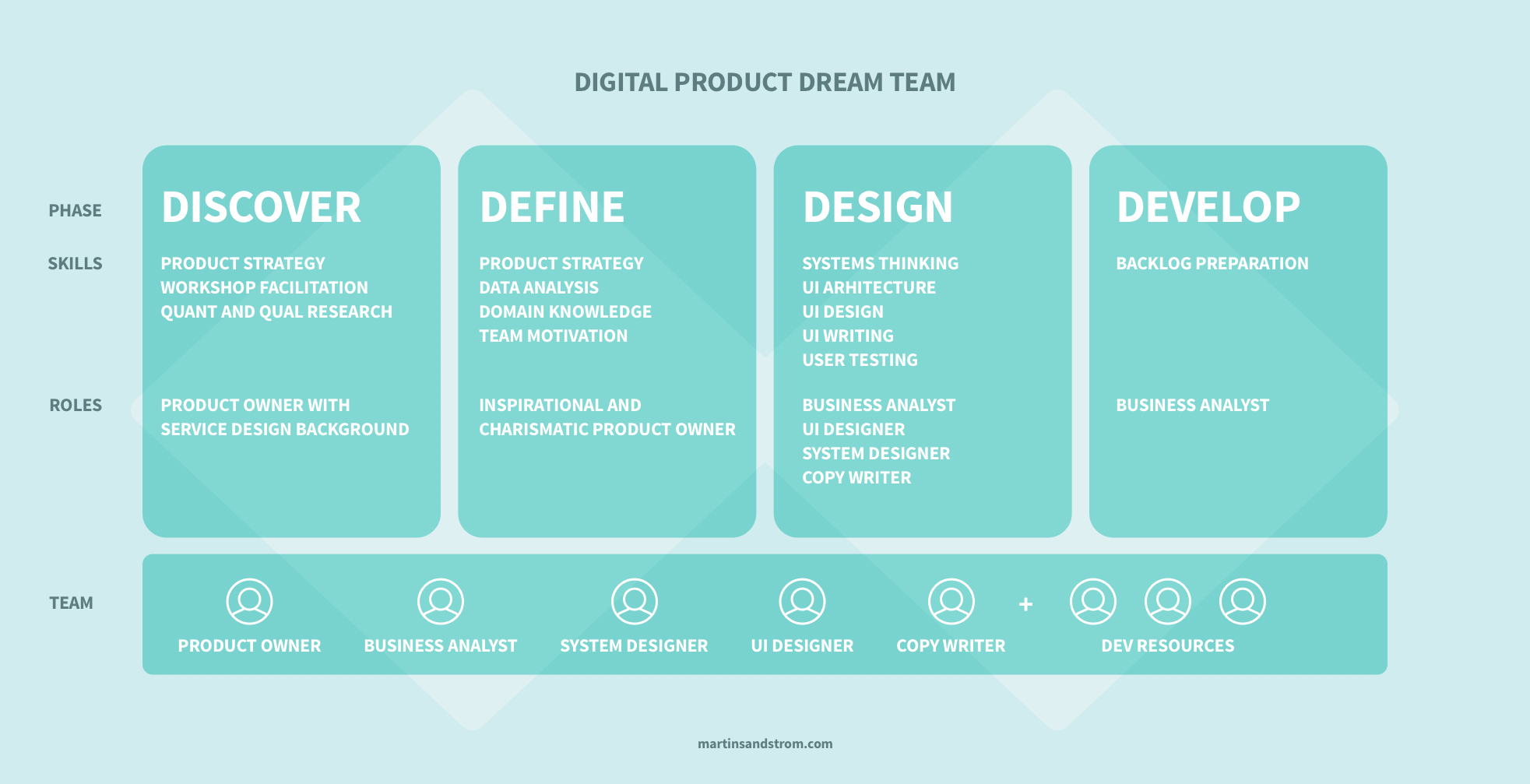

So when we do get permission to go and figure out what the right thing to do is, with horizon scanning, customer research, industry trend analysis, stakeholder interviews and all that good stuff, then the pressure is on. We better come up with some solid insights and strategies to show that designers can lead the discussion and do deserve a seat at the adult table.

Let’s uncover the world’s problems!

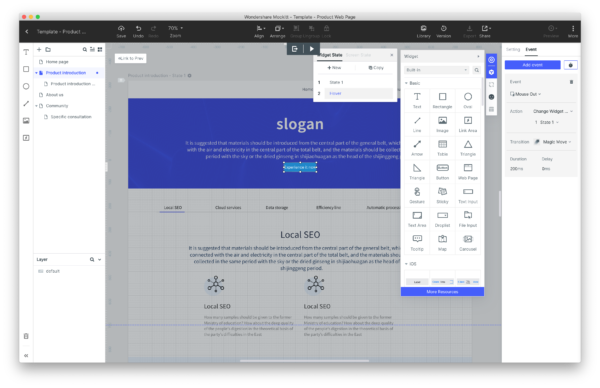

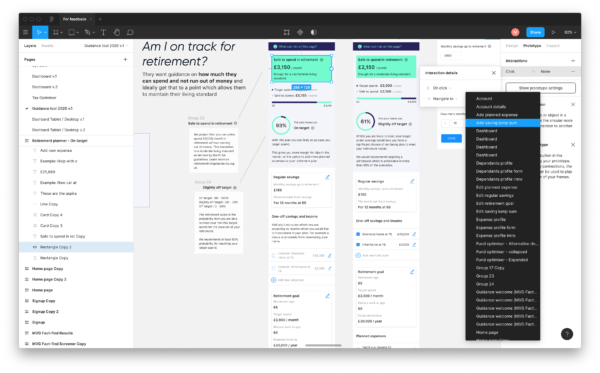

So off we go to run workshops, create hypotheses and research plans. We create How Might We statements and test prototypes. It’s messy and chaotic and although the unknown scares the heck out of us we feel so good about uncovering the untold truths about the industry we’re helping.

In the meantime our business stakeholders are starting to get impatient. Sure it was fun, albeit a bit awkward to be part of that LEGO-creation workshop, but when will we see something we can demo to the leadership team?

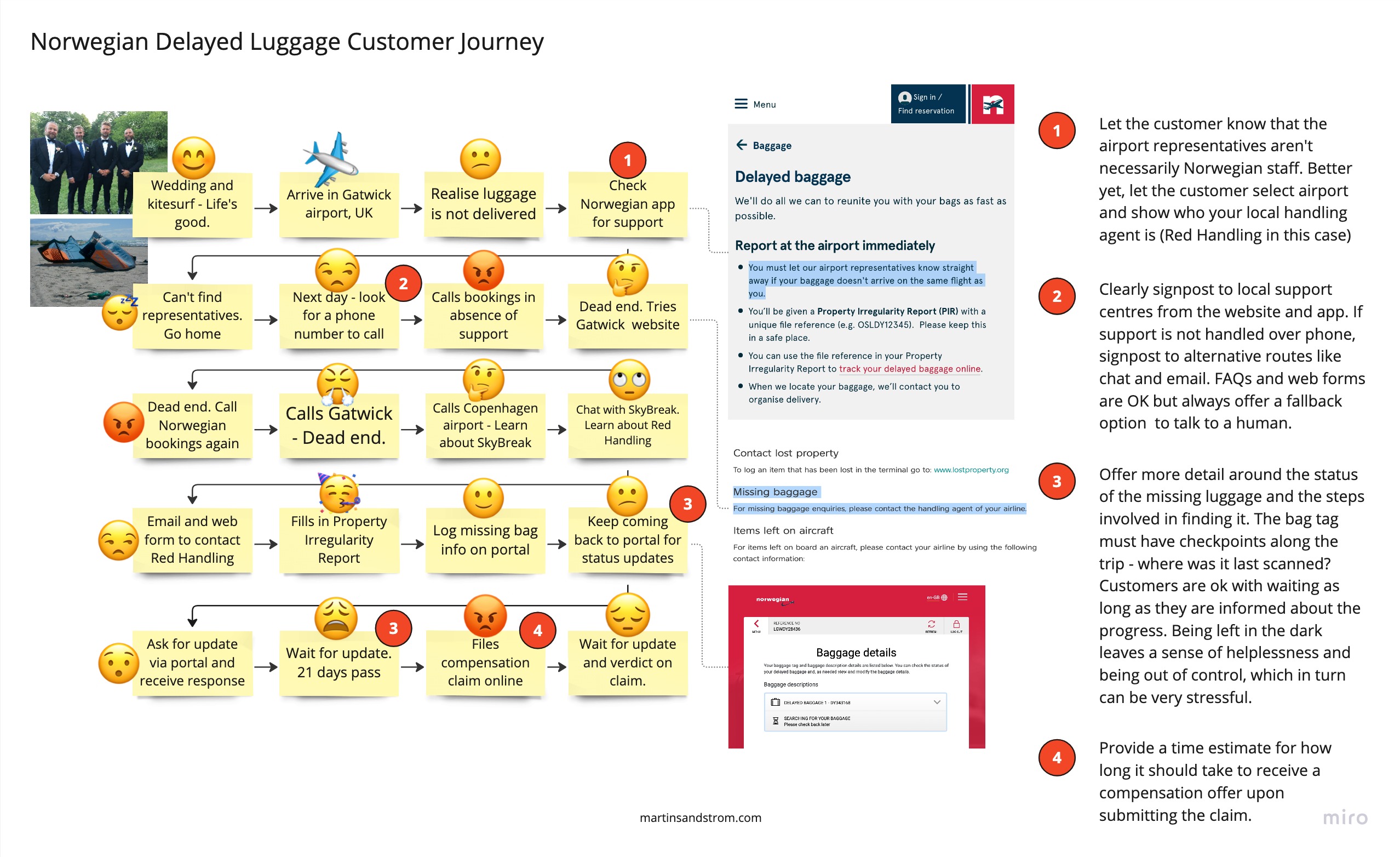

At one checkpoint meeting you’re told that a parallel work stream will start to look at quick wins. Get that low hanging fruit. You’re two thirds through your discovery and it’s starting to point towards operational inefficiencies due to manual workflows and incompatible computer systems. But no one seems to care. Your revealing insights are overshadowed by demos of the the new front-end UI which will fix a lot of cosmetic issues customers have been complaining about. Oh that low hanging fruit tastes so good! But is it nutritious?

Are we destined to be disillusioned?

Has this ever happened to you?

It happened to me and fellow designers and researchers, more than once, more than one company. You get the green light to define the problem space before jumping into solution mode, but when you’re presenting your findings and recommendations (if you even get that far) you’re told things like:

“We know that’s a problem, but we can’t do anything about it.“

“That’s out of our remit. If you want to change that you need to talk to the other teams.“

“The project needs to run its course – our sponsors are expecting delivery soon and we’re already behind.”

“We don’t have the budget to solve that this year. Are there any quick wins that will do for now?“

What should we do instead?

You can find project sponsors that are truly looking to solve root problems. That won’t be easy, but it would be the right thing to do. After all, if the research is done it’s done, and there will be someone in the organisation who is the right receiver of it. Maybe they’ll be open to continue the work you’ve started.

The easier approach is to not get stuck in discovery at all. As important it is to do discovery to find the right problem statement, it is even more important to understand how your involvement in the project came to be and what’s expected of you. To my previous point about designers needing to prove themselves, I think we’re sometimes too idealistic and design process driven (as opposed to business and delivery process driven).

Someone in the project team should obviously put their foot down straight away if you’re presenting a discovery plan that is too ambitious. This doesn’t happen because your stakeholders already have a set idea of what you’re supposed to bring to the project, so any plans shared and process explained aren’t actually fully understood. So they just let you get on with your proposed plan, assuming that you’re aligned with the project goals.

It’s time to come down from the high horse and be pragmatic about our discovery work. What we should focus our attention on is less about solving the right problem and more, way more, about how we can bring value to the project. I can hear the idealist designers twitching uneasily in their Eames chairs, but hear me out before you hit the dislike button.

When we understand why the project exists, who’s sponsoring it, how it fits with division and company objectives and what deliverables and results are expected, then we can propose a discovery phase if it’s not included already. This might be obvious to you already, but in my experience the discovery phase designers and researchers propose is often too front-heavy and ambitious.

All is not lost (Lean UX to the rescue?)

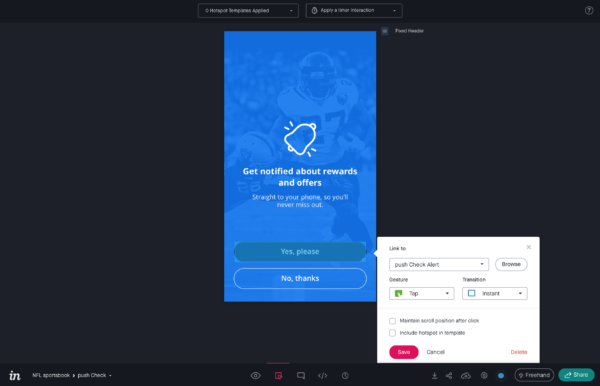

Of course we want to solve the right problem, but we have to do it within the constraints of the project, or it won’t go anywhere (as illustrated above). The approach might instead be to understand how we can quickly test and learn about the given problem space, and then course correct without pivoting completely. It might sting for idealist designers working this way, but corporate projects are often like oil tankers – the inertia and built up momentum will only respond to gentle and tactical input.

Here are some building blocks for this discovery approach:

- Understand why you are part of the project – what’s expected of you as a designer or researcher

- Understand the project goals and where they are coming from

- Find the smallest, substantial insight that would have impact on the solution – run a quick experiment to learn ‘just enough’ about it. Rinse and repeat.

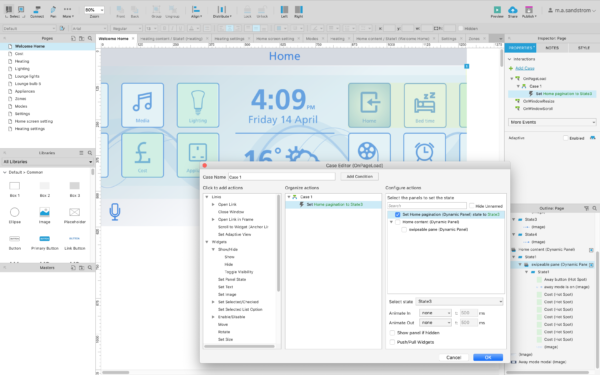

- Experiment with Lean UX methodology, as this is a similar approach, and see how you can use it in your discovery phase.

I haven’t personally had the chance to apply this Lean UX, fail-fast approach in a large discovery project yet. We use it in our agile teams all the time for product features, but here it’s applied to larger discoveries with potential impact on service and operational layers. I think it could work however – do let me know in the comments if it’s an approach you’ve been using and how effective it is in large scale projects.